Consumer Confidence in China: Premium Feels Risky

- Scale NZ

- Jul 25, 2025

- 7 min read

The decades of rapid growth are over, and consumer confidence in China remains low. But there is much that NZ exporters can do before resorting to discounts.

New Zealand’s exporters of food and drink to China already know the landscape has shifted. The boom-boom decades between 2000 and 2020 are well and truly over and in the face of a flat housing market, trade uncertainty and central policy dithering, the mood of consumers in our largest export market shows no sign of recovering soon.

Even though China’s economy is technically growing, the growth is slowing, and consumer sentiment has remained flat and cautious. People are watching their wallets. That doesn’t mean they have stopped buying food, but it does mean they are more selective, especially with premium products.

New Zealand brands count themselves as among the best on offer in China. But what happens when that isn’t enough anymore? Scale NZ’s Boom to Balance report (free download here) finds that even among high income residents of Shanghai, over one-third (37%) name affordability-related factors as a reason for not buying more NZ products. These factors include a need to cut back, a feeling that the price premium is not justified, as well as an objection to the sheer cost itself.

How do NZ brands stay relevant when their core market is suddenly price-sensitive? How can they keep their place in hearts and carts when price outweighs provenance?

Here are some suggestions for NZ exporters who want to hold their ground – without racing to the bottom.

1. Dequantify perceptions of ‘Value’

When consumer confidence dips, rationality surges and value gets reduced to a number: $/litre or 元/斤. It’s an understandable instinct but exacerbates the challenge for premium products. To “de-quantify” value is to give consumers a way of judging worth that goes beyond volume or weight.

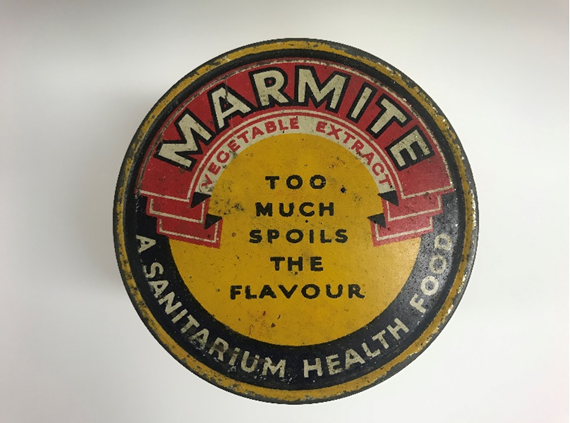

NZ exporters might find some century-old inspiration from Marmite in the 1920s. The product was known to be surprisingly potent for many users, hence the slogan. In addition to being counter-intuitive, hence highly differentiated in an FMCG context, and honest, this message profoundly moves the consumer’s conception of value:

FROM: “How much stuff do I get?”

TO: “How much of a hit do I get?”

Apply this to cheese. A sharper, more flavourful cheese costs more per gram, but far less is needed to transform a dish or complete a meal. The value isn’t in the size; it’s in the experience, the intensity, the satisfaction.

Do Chinese cheese eaters understand this?

Not really. China is still a young cheese market, and right now, blandness is the benchmark. Processed, mild, milky offerings dominate shelves and suit a palate that hasn’t yet grown up with dairy in the way Western markets have. But that also points to a white space – an opportunity for premium cheese makers willing to lead, not follow.

Tastier, sharper cheeses might seem like a hard sell at first. But they offer a clear point of difference, especially when supported by education, pairing suggestions, or moments of cultural relevance. These cheeses don’t just offer nutrition – they offer depth, savouriness, sophistication, and more impact per dollar than current offerings. Consumers need less to feel satisfied and that’s a value story, not just a flavour one.

Change the unit of comparison. Not how many grams, but how many moments

Educate on new and more affordable usage occasions

Impact per use, not cost per unit

Reframe Premium from Conspicuous Consumption to Personal Reward

In cautious times, consumers don’t stop spending, they just spend more deliberately. This is especially true in China, where premium brands once thrived on status signalling, but now face a more introspective consumer. China’s “common prosperity” campaign (共同富裕), launched in 2021 and relaunched in 2025, has arguably played a role in dampening consumer demand, with public institutions slashing entertainment budgets and officials avoiding conspicuous consumption altogether.

But the need to feel special cannot be extinguished; it has always had an individual dimension. The question of whether to buy a premium product therefore changes.

FROM: “Will this impress others?”

TO: “Does this feel worth it to me?”

For NZ brands, this opens the door to more emotionally resonant positioning. A food product isn’t just high quality – it’s a way to feel good, to feel nourished, or to enjoy a small moment of calm. Seafood from the pristine waters of New Zealand can be a health-giving ritual in times of stress. A spoonful of honey becomes a mid-afternoon mood lift. A soft cheese is a private indulgence at the end of a long day.

The challenge is to translate these quiet benefits into compelling, culturally relevant messaging that makes sense to me, for me. What does treat yourself mean for seafood, ice cream, wine, or butter in a Chinese context? What are the moments in a typical week where the product fits – not just functionally, but emotionally?

Premium needs to feel personal. Not excessive but earned.

Shift from Prestige to Personal Worth

Do not just sell ingredients; sell what it feels like to consume the brand

Articulate “treat yourself” or “you’ve earned this” in a way that resonates with your targets. Careful of clichés; aim for relevance.

3. Look Beyond the Distributor’s View of Market Signals

Distributors understand the local retail environment, navigate complex relationships, and are instrumental in getting the product onto the shelf. For many brands, especially smaller ones, they’re a lifeline and the primary source of feedback from the market. But in a period of low consumer confidence, it’s worth remembering that distributors see part of the picture, not the whole thing. Their insights tend to be very commercial, focus on what buyers want, what retailers are asking for, and what’s moving through the channel. That’s valuable but they’re observing effects, not causes. It does not capture the shifts in consumer sentiment or perceptions at ground level that shape buying behaviour. Distributors are naturally inclined towards discounting and will feel enormous pressure to do so when consumer confidence is under pressure.

Why are shoppers hesitating? What’s changed in how they define value? What’s being said online that never makes it into trade feedback? Does discounting make the most sense right now?

In China, the consumer moves faster than the channel. And brands that keep pace with changing attitudes are better placed to support their distributor, not just react to them. The best partnerships happen when marketers bring the consumer understanding and distributors brings channel expertise.

Bring your own perspective, look beyond trade data.

Ask your distributor to share the consumer insights they have used for their recommendations.

Validate and accept/reject alternative strategies, before pulling the trigger on discounts.

4. Design for Access

When consumers feel under financial pressure, they don’t necessarily reject premium – they just become more selective about how and when they engage with it. That’s why thoughtful product design is more powerful than reactive discounting.

For NZ exporters, the key move is to create lower-commitment ways to enter the brand. This might mean trial packs, smaller formats, or special editions that feel giftable and special, even at a reduced size. You’re not reducing your product, you’re right-sizing the experience for a market where caution is growing, but curiosity still exists.

Importantly, this approach keeps the brand’s equity intact. It says: “We understand where you’re at, and we’re still the same brand.” And in China, where smaller formats often carry higher perceived value (especially in gifting and online purchases), this means more than meeting the consumer halfway, it means meeting them where they already are.

Think about the cheese example again: a full wedge of a strong NZ cheddar might feel intimidating to a new buyer, but a beautifully wrapped 40g tasting size? That’s intriguing, non-threatening, and possibly the start of loyalty.

Access does not mean compromise. If designed well, smaller formats can be even more desirable – miniature moments of luxury in a market looking for both caution and quality.

Think access points, not price points.

Create smaller, more premium (yet lower-commitment) formats.

Show value with packaging and presentation that reflect thoughtfulness and quality.

5. Double Down on Gifting

In times of financial pressure, gifting doesn’t become less common – instead it becomes more meaningful. In a gift-giving culture, where reciprocity and social connection matter deeply, premium food can strike exactly the right tone: thoughtful, practical, and emotionally resonant. Especially when everyone understands that budgets are tight, a well-chosen gift of food or drink feels generous but not excessive, heartfelt without being showy.

This presents a real opportunity for New Zealand brands to extend their reach. A single purchase by a loyal, high-income consumer may be shared with extended family, colleagues, or friends – many of whom might never have encountered the product otherwise. Gifting becomes a multiplier.

Category examples abound. A sleek box of manuka honey carries wellness and status in one spoonful. A sample box of wines says celebration without extravagance. A gift-ready set of premium butters or cheeses could serve as a homey, heartfelt offering that surprises with both taste and thoughtfulness.

But the product must be designed for it. That means packaging that signals care and quality: distinctive, attractive, and clearly gift-appropriate. A gifted product is a brand ambassador. It enters homes with a story and leaves an impression that no online ad or shelf display could match.

Although consumer confidence is low, in a market like China, gifting is one of the few moments where premium still feels like the right thing to do.

Use gifting as trial, turning one purchase into multiple contacts with the brand.

Create packaging that signals care, quality and occasion.

Tailor the brand story to the gifting context.

Summary

New Zealand’s food and beverage exporters to China are operating in a more cautious, complex market than in decades past. Chinese shoppers haven’t stopped spending – but they are more deliberate, especially with premium purchases. While New Zealand brands are still well-regarded, being ‘the best’ is no longer enough. Price sensitivity is rising, even among high-income consumers, and exporters must now justify their value more clearly.

This doesn’t mean racing to the bottom. Instead, it calls for smarter strategies: de-quantifying value to shift focus from price per unit to experience per use; repositioning premium products as personal rewards rather than public status symbols; looking beyond distributor-driven responses; and adding value creatively without undermining brand equity. Accessible formats, thoughtful packaging, and smaller sizes can make premium products feel both attainable and special. And in a culture where gifting remains deeply embedded – even more so in financially uncertain times – products designed for generosity can extend reach beyond the core user and into wider circles of family, colleagues, and friends. Premium is still relevant. But today, it must feel personal, proportionate, and worth it.

_edited.png)

Comments